|

|

|

The Theory Of HyperText

Author:

B. Brown, 1999.

Copyright (1999). WebNet Journal: Internet Technologies, Applications & Issues. Distributed via the Web by permission of the WebNet Journal.

Abstract

This article attempts to underpin hypertext

development with theory. It is the view of the author that much

hypertext and web page development can be improved, if the

authors understand associated cognitive and educational theories.

Beginning with information theory, the model of web pages is discussed. This is followed by a brief overview of hypertext and the distinguishing features that separate hypertext from other forms of media. In comparing the print medium to that of web pages, the author attempts to show the distinctive nature of the medium, and how pages must be designed differently in order to take advantage of these characteristics.

Finally, the author looks at how flow and constructivist theory can be applied to the design of web pages. In summary, the author concludes that an understanding of associated theories can lead to better hypertext and web page designs.

![]() Shannon's model of

communication

Shannon's model of

communication

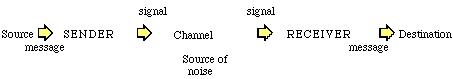

In 1948, a model of communication was proposed by

Claude Shannon. Shannon worked for the Bell Telephone Company in

America, and was concerned with the transmission of speech across

a telephone line. Warren Weaver, in association with Shannon,

wrote a preface to this model and it was published as a book in

1949. Weaver saw the applicability of Shannon's model of

communication to a much wider sphere than just telephony, and it

has served as a basis for explaining communication since that

time.

In any communication there is noise, which affects the message as it travels across the channel from the sender to the receiver. Shannon proposed building in redundancy, which was added to the transmitted message in order for it to be reliably detected at the receiver. When we apply this model to printed pages, it looks like

| Message | The idea, thought expressed by the author |

| Source | The words on the page |

| Sender | The transmitting device, the reflection of light that makes the words visible |

| Channel | The medium the message travels over, air |

| Receiver | The receiving device, the retina |

| Destination | The brain, the consciousness of the reader |

This however is a very simplistic approach. It does not take into account all the cultural and experiential differences between individuals, or address how each person makes sense of what they see (the process of interpretation and understanding). There are also those that would argue that the message is not the idea expressed by the author.

We can identify certain aspects of this model when applied to the printed medium. These aspects are

The model is an important one. It helps us try to understand the underlying principles of communication. Redundancy is important if we want the message to be understood. In trying to apply the model to print media and hypertext, we can learn valuable lessons about how to improve the process of communication.

Hypertext Overview

The Oxford English Dictionary gives the origin of

the word text as Latin, with the meaning "that

which is woven". Hypertext, for the purposes of this article,

is described as non-sequential written text that allows branches

and multiple paths to be selected by the reader. The essential

point here is control by the reader and the linked arrangement of

the information being presented. Sequential flow imposed by

authors in the printed medium is replaced by flow initiated by

the reader.

|

Vannevar Bush is often associated with the idea of hypertext. As early as 1945, Bush proposed his MEMEX machine in an article entitled "As we may think". The idea was to create a machine that would link or associate material for reference purposes. As items of information became linked, this would permit the creation of new forms of information based on these links. |

| "Wholly new forms of encyclopedias

will appear, ready made with a mesh of associative trails

running through them, ready to be dropped into the memex

and there amplified." As we may think, Vannevar Bush, 1945 |

Today we see Vannevar Bush's predictions and ideas in practice. What else is Yahoo but a great association of links of information that has created a new form of information; the searchable web of associations.

Douglas Engelbart and Ted Nelson (who is said to have coined the phrase hypertext in 1962) are two of the people involved in the early development of hypertext systems. Engelbart (famous for the development of the mouse when working at the Stanford Research Center in 1963) saw hypertext as a necessary component of any system designed to improve communication.

| "and that you can jump and look at

different abstract levels.. we've got this extremely

flexible way in which computers can represent modules of

symbols and can tie them together with any structuring

relationship we can conceive of" Douglas Engelbart, 1992 |

Nelson saw hypertext as a tool that enabled the author of a text to present multiple versions at the same time, in order to compare them.

| "Allows you to see alternative

versions on the same screen on parallel windows and mark

side by side what the differences are." Ted Nelson, 1993 |

In using hypertext, both Engelbart and Nelson see an improvement in the communication process, by offering alternative ways of viewing and associating information. Shannon's model of communication, being a one-way model, indicates that both structure and flow are important aspects. However, it is limited in application to hypertext systems, as it cannot accommodate the cybernetic relationship that exists by the user interaction performed by link selection and resultant change in flow due to that link selection.

Unlike a printed medium, hypertext allows a reader to enter and exit at multiple points. One cannot assume prior reader knowledge of the inherent structure within the hypertext document, and so it makes it harder to build on previous content in the way that printed pages can.

In summary, we can give the following characteristics of hypertext as

![]() Aspects of Print Medium

Aspects of Print Medium

Since Gutenberg and the printing press, the

printed page has allowed man to not only accumulate knowledge,

but also to cross-reference knowledge. There has been an

information explosion, as ideas written down are built on and

expanded by others. This period of scientific research based on

the printed medium has amassed a vast knowledge base for mankind.

The following table lists some of the aspects of the printed medium.

| structure | A page or book has structure, evidenced by words, sentences, paragraphs, pages, titles and an index. We read in a certain way, the structure of the written word imposes that on us, and we read according to its structure. An author also structures information, building concepts on earlier concepts, like lego building blocks, eventually revealing the big picture. |

| non interactive (static) | It is not possible to query the mind of the author. The ideas and thoughts, once committed to paper, take on their own meaning and are re-interpreted by each new reader. We do not have the ability to go directly to the source and query the ideas and expressions of words used by the author. |

| context based | A reader reads according to the structure of the medium, and this is sequentially based. An author relies upon the fact that a reader has already encountered ideas expressed earlier, building up a schemata of terms and prior experience. Plots are gradually revealed, leading to climaxes and anti-climaxes. Readers are assumed to know what was written earlier and have that information readily available, serving as a reference for that which is to come. |

| time based | The reader turns each page; maintains

eye movement across and down the page. Each break serves

as both an isolator between sections and a connection

point to the next (whether between sentences, paragraphs

or pages). These pauses are essential to the thought

process, allowing time for reflection and assimilation of

information (by allowing the brain time to organize the

ideas into its existing framework). We also consider that the author and the reader are separated by time. The communication between them is said to be asynchronous. Indeed, they can be separated by generations, the author long having passed away. The asynchronous nature of the communication precludes interaction between the author and reader, making the communication non-interactive (passive). |

| spatially based | The reader is separated from the author spatially. They are not located in the same physical space. This separation precludes any interaction between them. |

| reflective | The page is flat, is within the visual depth of the reader, and opaque. It is designed to reflect the letters and words so that they are clearly discernible with minimum effort by the reader. A symbol on the page is just that, a symbol, and A is an A. It cannot take on any other meaning in any other context, an A is always an A. |

| private | Most of the time, reading is not a group thing. It is a private activity. We try to imagine and grasp the ideas and get caught up in the story line as expressed by the author. The effective use of words chosen by the author is designed to elicit the desired emotional responses within the reader. There is no intermediary between the reader and the book, rather a direct connection is established between the words on the page and the reader. |

![]() Aspects of Hypertext

Aspects of Hypertext

In conventional printed material, structure is

maintained by the use of pages, chapters and table of contents. A

reader, due to the sequential nature of the medium, has assembled

past associations with previously encountered material. This

helps to create an internally referenced structure in the reader's

mind. With hypertext, the structure is often created or imposed

by the author. This is done using navigation aids and hyperlinks.

Yet, this structure will often conflict with the navigational

structure created by the reader. The very nature of hypertext

gives the reader the freedom to choose his or her own path.

Hypertext documents offer the reader the choice of progression, but this progression can lead to reader disorientation. A reader may not know where they are, and thus structure becomes important in hypertext. Concepts such as maps, frames, and opening of new windows help to maintain structure, providing a reference point to which the reader can return.

Hypertext documents begin to become modular, without reliance upon previously associated material, each linked to others in a mesh type arrangement rather than a sequential flow. The reader can diverge, explore, then return and continue. This raises problems of navigation and structure. Each section becomes both dependent and independent of other sections in the document. Multiple exit and entry points help create reader disorientation. One way of providing digression is the use of pop-up boxes rather than separate sections, as illustrated above in the section on Vannevar Bush. This disorientation can be thought of as noise in the Shannon model discussed earlier.

The scrolling of a page causes breaks in reader concentration. The nearest parallel we have in printed material is the turning of the page. It requires a physical act involving an activity other than reading. The users focus moves to the scroll bar, and the mouse is positioned to select the scroll bar and drag the window down (or the PGDN button is pressed). Information in hypertext needs to be presented based on one idea per paragraph. Readers scan hypertext documents, and they do not use the same reading techniques as those used for printed material. Key points should be clearly visible, using bold titles to separate these from text (so they can be quickly located by the reader) or bulleted.

Each hyperlink represents a shift in reader focus. Each new link (especially those that transport to material written by another author) exposes the reader to different navigational and structural contexts, leading to disorientation (of course the answer is not to link to anything, but then it would cease to be hypertext). The reader becomes free from the author, merging the creations of other authors into the reader's vision of the accumulated material. Myriad sources allow this creation process to take place (some might use the term synthesis of information). By creating reference links, the author allows the reader to gather additional material and synthesis this material into their own framework of understanding.

The use of reference links inserted by the author also serves another purpose. It allows the reader to see the texts that influenced the author and where those ideas or content came from, or how they were re-interpreted by the author. With printed material, this is very difficult. Hypertext provides immediate access to such reference material (assuming they are on the Internet).

The pace of hypertext is quick. It involves scanning and searching more than reading. Users do not read; they click; they jump; they transport; exploring divergent paths on a million different highways leading to a billion different destinations. Contents change rapidly. They are here today, changed tomorrow, referenced next week, not found next month. Permanence is hard to find on the web.

Pages come into being upon display. Who can say that an A in memory is actually an A? Written on a page it retains its meaning, but in digital form, stored in memory, written in a file, transmitted across the Internet, it is only a sequence of bits without meaning. The reader derives the meaning when it impinges upon the reader's sight and is interpreted with the prior associations of symbols and meanings that the reader has. It shifts from distal to proximal and comes alive in the thoughts of the reader.

Hypertext mimics the way the brain works, by association. The brain, with its myriad connections of neuron pathways, associates information together.

| "The human mind operated by

association. With one item in its grasp, it snaps

instantly to the next that is suggested by the

association of thoughts, in accordance with some

intricate web of trails carried by the cells of the brain." Vannevar Bush, 1991 |

Benjamin Lee Whorf, perhaps more famous for the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, saw the connection of ideas as having an accidental character as the subject jumped from idea to idea in a non-controlled way. Whorf saw the association of ideas as being controlled and following an orderly progression along related paths.

| "Connection is important from a

linguistic standpoint because it is bound up with the

communication of ideas." Benjamin Lee Whorf, 1956 |

What has this got to do with hypertext? What form does hypertext most readily support? Connection or Association? Or Both?

Hypertext supports the connection of ideas. The use of hypertext-linked documents (and reference links) allows the reader to jump from content to content (idea to idea, at the whim of the reader). Hypertext supports the association of ideas. Author imposed navigation structure provides for this, by virtue of content pages and pop-up message boxes. According to Whorf, a hypertext document relying upon connection of ideas would be a more effective model of communication than one based on an association of ideas.

Hypertext supports Intertextuality. Intertextuality is derived from the Lation intertexto, meaning "to intermingle while weaving". The theory is based on the assumption that writings derive their meaning from their relationship to other writings, and not by reference to an external reality. Writings by the author are influenced by all that they have read and experienced (their cultural context). In the printed medium we see evidence of this by use of footnotes.

Hypertext emphasizes and embraces intertextuality in a way that printed pages cannot. Provision of reference links exposes the reader to the material used by the author in the construction of the document. The reader is thus more able to see the threads that have been woven together by the author in the creation of the document. This material is often accessible immediately on the Internet. Hypertext documents become woven mosaics of multiple texts. An an example, you can see the threads of thought about intertextuality written here in this document as a re-interpretation of those texts listed in the reference section.

| "Any text is a new tissue of past

citations. Bits of code, formulae, rhythmic models,

fragments of social languages, etc., pass into the text

and are redistributed within it, for there is always

language before and around the text. Intertextuality, the

condition of any text whatsoever, cannot, of course, be

reduced to a problem of sources or influences; the

intertext is a general field of anonymous formulae whose

origin can scarcely ever be located; of unconscious or

automatic quotations, given without quotation marks." Roland Barthes, 1981 |

Hypertext supports asynchronous communication. In this sense, hypertext is similar to and gives all the functionality of the printed medium.

Hypertext supports synchronous communication. Hypertext (by linking to applications that support synchronous communication) extends and goes beyond the printed medium. It now becomes possible to have direct contact with the author, even face to face. This has the potential for creating a much richer environment for communication that that currently possible with asynchronous forms of communication. This aspect of interaction, whether as one to many or many to many cannot be supported by the printed medium and is one area where hypertext (and web pages) can significantly enhance communication.

Hypertext supports centering and de-centering. The use of hyperlinks means that the center of focus continually shifts under the control of the reader. The reader becomes an active component in the communication process. The reader can choose his or her own center of investigation. It frees the reader from being locked into the author's structure and navigational preferences (this is an important element in constructivism theory, discussed later in this document).

![]() Flow Theory

Flow Theory

Hoffman and Novak

proposed in 1996 that a user is more likely to revisit a web site

if that site facilitates a feeling of immersion (flow). All of us

have at some time or other become immersed in an activity, such

as reading a book or watching television. We become so involved

in the activity that we become unaware or less conscious of the

activities happening around us. Recent research into Internet

user behavior on-line has begun to focus on this immersion aspect

called "flow theory".

Models for testing and measuring flow have been proposed. The use of site analyst tools that can track user behavior on-line (monitor their click usage, the links they select, how long they view a page) can construct a behavior pattern for each user. This can then be fed back into the web site and allow personalized customization of information dependent upon prior behavior of the individual.

Some basic elements that has come out of this research is that interactivity, chat, and personalization of content are all factors that lead to increased flow. Other aspects that can increase flow are relevant and up-to-date information that is short, concise, easily read and scannable (see Morkes, J. & Nielsen, J. Concise, 1997).

![]() Constructivism

Constructivism

Schema theory is about structures, in particular,

about structures that are created by the individual as part of

the learning process. Each individual associates knowledge as

structures in their memory. New knowledge is added to existing

structures, or existing structures are restructured. In

constructivism, students build mental models or constructs based

on previous knowledge by dynamically interacting during the

learning process.

The student accepts responsibility for learning, and the teacher becomes more of a facilitator or guide.

Hypertext supports constructivism by allowing the reader to take control of the learning process. Web pages in particular are an example of reader initiated learning. Readers try to discover principles and knowledge for themselves. The use of synchronous methods of communication supports an active dialog between the author and the reader. Les Vygotsky was a pioneer of constructivism.

![]() Elaboration Theory

Elaboration Theory

Elaboration theory is a theory about how to

structure information for learning purposes. Material is

organized from simple introductions to more complex material. In

each section, associations with the previous and next section are

made so that the student can clearly see the progressive path

through the material and the linkage between the sections.

Summaries are provided at the end of each section.

Similar to constructivism, it emphasizes the necessity to develop a meaningful context for the student so that ideas and concepts can be assimilated. Summaries, introductions and linkages to other material provide this context for the student.

Hypertext supports elaboration. Material is easily constructed according to this model of instruction using web pages and hyperlinks. Links to previous material provide reference and revision function for the reader. Use of headings and sections clearly delineate the material according to elaboration principles.

![]() Shannon's Model and Web

Pages

Shannon's Model and Web

Pages

When we apply Shannon's model of communication to

web pages, the result is shown in the following table.

| Message | The page content |

| Source | The html page, as a sequence of bits, images and links |

| Sender | The web server |

| Channel | The medium the message travels over, the Internet |

| Receiver | The modem |

| Destination | The computer screen |

Noise is possible at any point in the connection between the source and the destination (though for Shannon noise occurred only in the channel). What do we define as noise? In this instance we can think of noise as any factor that prevents effective communication between the source and the destination. This can be anything from poor page layout, incorrect choice of text fonts, colors and sizes, to lack of hyperlinks and inadequate navigational structures.

![]() Conclusions

Conclusions

Some of the theory discussion above focused on

fundamental concepts of association, structure and design. These

basic principles help authors design better web pages. In this

article we have introduced a theoretical base for hypertext

development, looking at elaboration theory, intertextuality,

association, connection and constructivism.

All these theories relate to communication and outline basic principles that can be used by the hypertext author to improve the communication of ideas and concepts. By looking at web design within a theorectical framework, it becomes possible to elucidate basic principles that will enhance the communication of any web site. All design should be grounded in theory, and tested in practise. The charming character of the web medium is that there are so many of us doing it.

![]() References and Further

Reading

References and Further

Reading

Bardini, T. (1997). Bridging the gulf: From

hypertext to cyberspace. Retrieved March 12, 2000 from the World

Wide Web: http://www.ascusc.org/jcmc/vol3/issue2/bardini.html

Barthes, R. (1981). "The Theory of the Text." Untying the Text. Ed. Robert Young. Boston: Routledge and Keagan Paul. 31-47.

Birkets, S. (1994). The Gutenberg Elegies. Boston. Faber and Faber. Retrieved March 12, 2000 from the World Wide Web: http://www.obs-us.com/obs/english/books/nn/bdbirk.htm

Bush, V. (1991). As we may think. In J. M. Nyce & P. Kahn (Eds.), From memex to hypertext (pp. 85-110). Reprinted from the Atlantic Monthly, 176 (1) (1945), 641-649.

Eklund, J. (1996). Cognitive models for structuring hypermedia and implications for learning from the world-wide web. Retrieved March 12, 2000 from the World Wide Web: http://www.scu.edu.au/sponsored/ausweb/ausweb95/papers/hypertext/eklund/index.html

Engelbart, D. C. (1992). Personal interview with Bardini, T., 12/15/1992, Menlo Park, CA. Retrieved March 12, 2000 from the World Wide Web: http://www.ascusc.org/jcmc/vol3/issue2/bardini.html

Hoffman, D., & Novak, T. (1996). Marketing in Hypermedia Computer-Mediated Environments: Conceptual Foundations," Journal of Marketing, 60 (July), 50-68.

Inder, R. (1994). Applying Discourse Theory to aid Hypertext Navigation. Retrieved March 12, 2000 from the World Wide Web: http://www.hcrc.ed.ac.uk/gal/Publications/echt94.html

Morkes, J. & Nielsen, J. (1997). Concise, SCANNABLE, and Objective: How to write for the web. Retrieved March 12, 2000 from the World Wide Web: http://www.useit.com/papers/webwriting/writing.html

Nelson, T.H. (1993). Personal interview with the Bardini, T.,

3/27/1993, Sausalito, CA. Retrieved March 12, 2000 from the World

Wide Web: http://www.ascusc.org/jcmc/vol3/issue2/bardini.html

Shannon, C. & Weaver, W. (1949). The Mathematical Theory of Communication. Urbana. University of Illinois Press.

Whorf, B. L. (1927). On the connection of ideas. Letter to Horace B. English, first published in 1956 in Language, thought, and reality (pp. 35-39). Cambridge MA: MIT Press.

Last Modified: March 12, 2000

Author B. Brown,

1999

Copyright (1999). WebNet Journal: Internet

Technologies, Applications & Issues. Distributed via the

Web by permission of the WebNet Journal.